JavaScript Closures Explained for Beginners (Simple & Clear Guide)

What Is a JavaScript Closure?

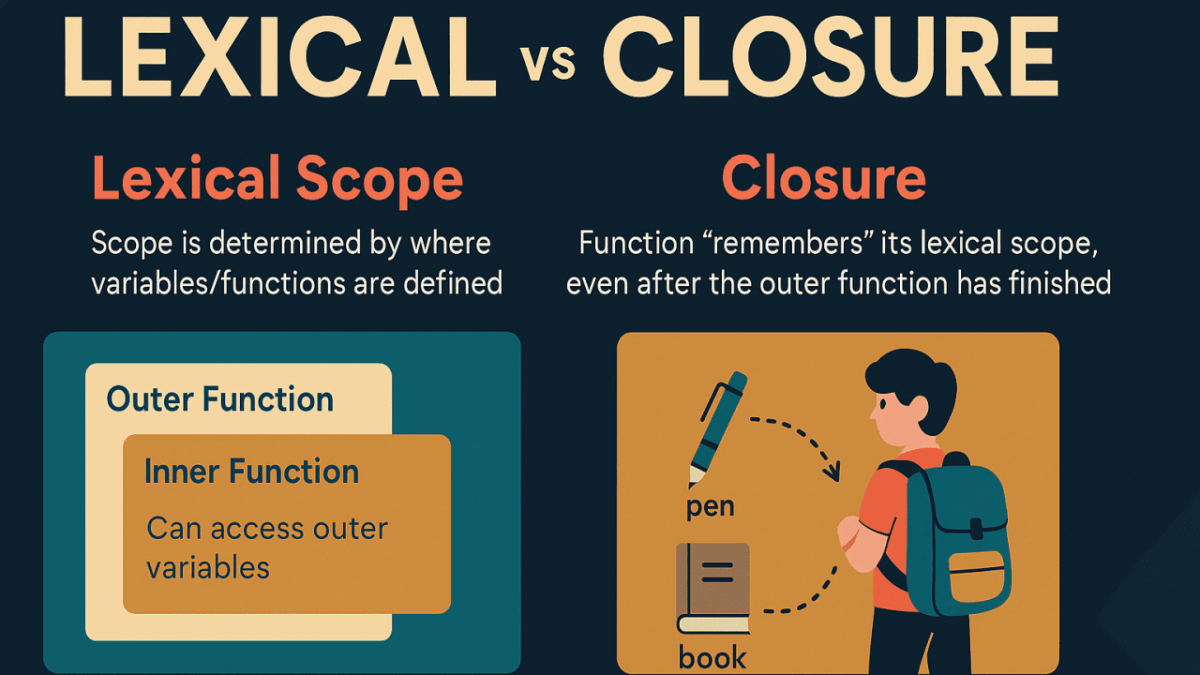

A closure is a function that retains access to its outer function's variables, even after the outer function has finished executing. More formally (but still in simple terms), a closure is a function that remembers the variables from its outer scope, even after that outer scope is gone. This lets the function “close over” its environment.

Introduction: The Reality of JavaScript Closures

Let’s be honest.

JavaScript closures are one of those topics that almost everyone finds confusing at first. If you search online, you’ll see long debates, deep terminology, and people arguing over definitions like execution context, lexical environment, garbage collection, and scope chains. That alone is enough to make beginners feel like they are already behind.

Here’s the reality most tutorials don’t tell you:

You are not supposed to fully “get” closures on day one.

Closures are not something you master by memorizing a definition. They are something you experience while building real projects.

Think of closures like this:

A function remembers the variables around it from the place where it was created — and it can still use them later, even when that place is no longer running.

That’s it. No magic. No panic.

So in this article, we will not overcomplicate things.

We’ll focus on understanding closures the way beginners actually learn, gradually, practically, and without fear.

Before You Learn Closures: What You Actually Need

You do not need to be an expert in JavaScript to start learning closures.

Prerequisites:

How functions work in JavaScript

Function scope vs global scope

Variables (let, const, var) at a basic level

Returning a function from another function

That’s enough to get started.

About Execution Context (Don’t Worry Too Much Yet)

You might hear people say:

“You must understand execution context before closures.”

That statement is partially true, but often misunderstood.

Yes, execution context helps explain why closures work.

If you’ve already read my blog on JavaScript Execution Context, that’s great, you have an advantage.

At the beginner stage:

You don’t need to visualize the call stack perfectly

You don’t need to memorize lexical environment diagrams

You don’t need to worry about garbage collection optimizations

All you need is awareness, not mastery.

Building Your Foundation Gently

Let's Start With Something Familiar

Before we talk about closures, let's remind ourselves how regular functions work:

function sayHello() {

let greeting = "Hello!";

console.log(greeting);

}

sayHello(); // "Hello!"

console.log(greeting); // Error: greeting is not definedThis makes sense, right? The variable greeting only exists inside sayHello. Once the function finishes, greeting disappears.

Now Let's Make It Interesting

Watch what happens when we put one function inside another:

function outer() {

let message = "I'm from outer!";

function inner() {

console.log(message); // Can access message!

}

inner();

}

outer(); // "I'm from outer!"The inner function can see message from outer. This feels natural because inner is physically inside outer. But here's where it gets magical...

The Magic Moment: When Closures Reveal Themselves

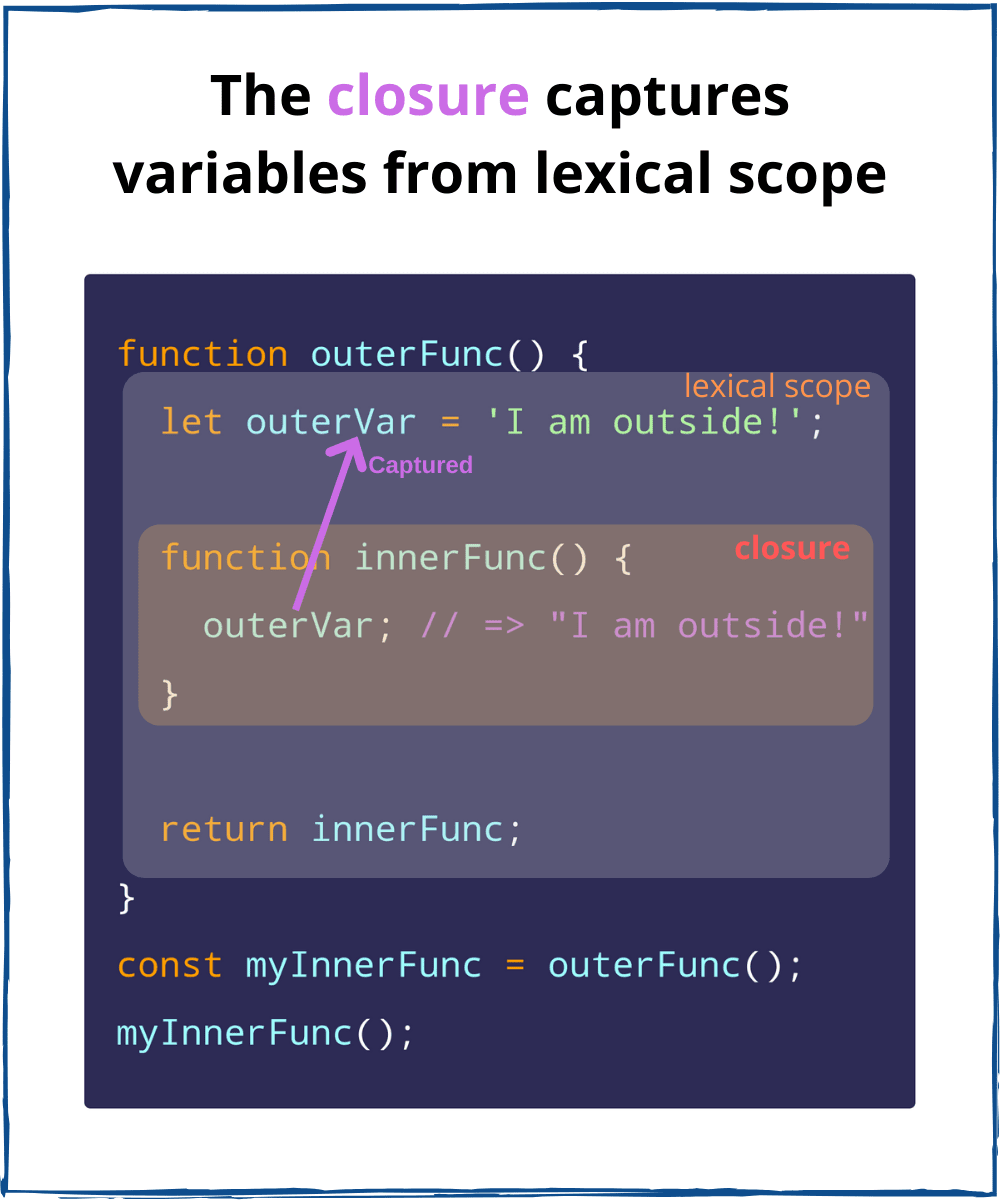

function outer() {

let message = "I'm from outer!";

function inner() {

console.log(message);

}

return inner; // Return the function itself

}

const myFunction = outer(); // outer() runs and finishes

myFunction(); // "I'm from outer!" — Wait, what?Pause and think about this: The outer() function has finished running. Normally, message should be gone, cleaned up, deleted from memory. But when we call myFunction(), it still prints the message!

This is a closure. The inner function "closed over" the message variable, keeping it alive even after outer finished.

Breaking It Down Even Further

Let's trace through what happens step by step:

Line 1-7: We define outer() with a variable and an inner function

Line 9: We call outer(), which creates message and returns the inner function

Line 9 (continued): outer() finishes executing, normally everything inside would be destroyed

Line 10: We call myFunction() (which is the inner function)

Line 10 (magic): The function still has access to message from step 2!

The inner function brought message with it, like packing a suitcase before leaving home.

The Simple Rule to Remember

When a function is created inside another function, and it uses variables from that outer function, it forms a closure. The inner function will always remember those variables, no matter where or when you call it.

A Practical Example You'll Understand

Let's create a simple counter:

function createCounter() {

let count = 0;

return function() {

count = count + 1;

return count;

};

}

const counter = createCounter();

console.log(counter()); // 1

console.log(counter()); // 2

console.log(counter()); // 3Each time you call counter(), it increments and returns the same count variable. That variable persists between calls because the function "remembers" it through closure.

Why this is useful: You've created persistent state without using global variables or complex objects. The count is private, only the function can access it.

Real-World Applications (Where Closures Shine)

Now that you understand the basics, let's see where closures become genuinely useful in real applications.

Use Case 1: Creating Private Data

Sometimes you want data that can only be changed through specific methods:

function createBankAccount(startingBalance) {

let balance = startingBalance;

return {

deposit: function(amount) {

balance = balance + amount;

console.log(`Deposited $${amount}. New balance: $${balance}`);

},

withdraw: function(amount) {

if (amount <= balance) {

balance = balance - amount;

console.log(`Withdrew $${amount}. New balance: $${balance}`);

} else {

console.log("Insufficient funds!");

}

},

checkBalance: function() {

console.log(`Current balance: $${balance}`);

}

};

}

const myAccount = createBankAccount(100);

myAccount.deposit(50); // Deposited $50. New balance: $150

myAccount.withdraw(30); // Withdrew $30. New balance: $120

myAccount.checkBalance(); // Current balance: $120

// This won't work - balance is private:

console.log(myAccount.balance); // undefinedThe balance variable is completely protected. Users can't directly modify it, they must use your methods. This is data encapsulation through closures.

Use Case 2: Event Handlers That Remember Context

Imagine setting up multiple buttons, each with different behavior:

function setupButtons() {

const actions = ['save', 'delete', 'edit'];

actions.forEach(function(action) {

const button = document.getElementById(action + '-btn');

button.addEventListener('click', function() {

console.log('Performing action: ' + action);

performAction(action); // Each closure remembers its own action

});

});

}Even though the loop finishes quickly, each click handler remembers which action it belongs to. That's closures preserving context for later use.

Use Case 3: Function Factories (Creating Customized Functions)

You can create specialized functions from a general template:

function createGreeter(greeting) {

return function(name) {

console.log(greeting + ', ' + name + '!');

};

}

const sayHello = createGreeter('Hello');

const sayHi = createGreeter('Hi');

const sayHowdy = createGreeter('Howdy');

sayHello('Alice'); // "Hello, Alice!"

sayHi('Bob'); // "Hi, Bob!"

sayHowdy('Charlie'); // "Howdy, Charlie!"Each function "remembers" its specific greeting. You've created three different greeters from one factory function.

Use Case 4: Module Pattern (Organizing Code)

Closures help create self-contained modules:

const ShoppingCart = (function() {

// Private data

let items = [];

let total = 0;

// Private function

function calculateTotal() {

total = items.reduce((sum, item) => sum + item.price, 0);

}

// Public interface

return {

addItem: function(item) {

items.push(item);

calculateTotal();

console.log(item.name + ' added to cart');

},

getTotal: function() {

return total;

},

getItemCount: function() {

return items.length;

}

};

})();

ShoppingCart.addItem({ name: 'Book', price: 15 });

ShoppingCart.addItem({ name: 'Pen', price: 3 });

console.log(ShoppingCart.getTotal()); // 18

console.log(ShoppingCart.items); // undefined - private!Only the methods you explicitly return are accessible. Everything else stays private through closures.

Common Challenges, Myths & Pitfalls

Challenge 1: The Infamous Loop Problem

This is probably the most common closure mistake:

// This won't work as expected:

for (var i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i);

}, 1000);

}

// Prints: 3, 3, 3 (not 0, 1, 2)Why? All three functions share the same i variable. By the time they run (after 1 second), the loop has finished and i equals 3.

Easy fix: Use let instead of var:

for (let i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(i);

}, 1000);

}

// Prints: 0, 1, 2Why it works: let creates a new i for each iteration, so each closure gets its own separate variable.

Challenge 2: Stale Closures in React

React developers often encounter this:

function Counter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

useEffect(() => {

setInterval(() => {

console.log(count); // Always logs 0, not the current count!

}, 1000);

}, []); // Empty array means this closure is created only once

return <button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>Increment</button>;

}Why? The closure was created when count was 0, and it remembers that original value.

Solution: Use functional updates:

setInterval(() => {

setCount(prevCount => prevCount + 1); // Uses current value

}, 1000);Myth 1: "Closures Are Complicated and Rare"

Truth: Closures happen all the time! Every callback, every event handler, most React hooks, they all use closures. You've been using them without knowing it.

Myth 2: "Closures Copy Variables"

Truth: Closures keep references to variables, not copies. If the variable changes, the closure sees the new value (unless it already captured it in a specific way).

Myth 3: "Closures Are Slow and Waste Memory"

Truth: Modern JavaScript engines optimize closures heavily. Unless you're creating millions of closures, performance is negligible. The benefits far outweigh any minimal overhead.

Step-by-Step Implementation Guide

Let's walk through creating something useful with closures from scratch.

Step 1: Identify When You Need a Closure

Ask yourself:

Do I need data that persists between function calls?

Do I want private data that's not globally accessible?

Am I creating similar functions that differ only in configuration?

Do my callbacks need to remember context?

If yes to any, closures might help.

Step 2: Start With a Simple Example

Begin with the basic structure:

function createSomething() {

let privateData = 'initial value';

return function() {

// Use or modify privateData

};

}Step 3: Build Your Use Case

Let's create a simple task tracker:

function createTaskTracker() {

let tasks = [];

let nextId = 1;

return {

addTask: function(description) {

const task = {

id: nextId,

description: description,

completed: false

};

tasks.push(task);

nextId = nextId + 1;

console.log('Task added:', task);

},

completeTask: function(id) {

const task = tasks.find(t => t.id === id);

if (task) {

task.completed = true;

console.log('Task completed:', task);

}

},

getTasks: function() {

return tasks.map(t => ({...t})); // Return copies, not originals

}

};

}

// Usage:

const myTasks = createTaskTracker();

myTasks.addTask('Learn closures');

myTasks.addTask('Build a project');

myTasks.completeTask(1);

console.log(myTasks.getTasks());Step 4: Test Edge Cases

Try:

Creating multiple instances (they should have separate data)

Rapid successive calls

Passing the function around to different contexts

const tracker1 = createTaskTracker();

const tracker2 = createTaskTracker();

tracker1.addTask('Task for tracker 1');

tracker2.addTask('Task for tracker 2');

// Each has its own private data

console.log(tracker1.getTasks()); // Only has tracker1's task

console.log(tracker2.getTasks()); // Only has tracker2's taskStep 5: Add Error Handling

Make your closure robust:

function createSafeCounter() {

let count = 0;

return {

increment: function() {

count = count + 1;

return count;

},

decrement: function() {

if (count > 0) {

count = count - 1;

return count;

} else {

console.log('Cannot go below zero');

return count;

}

},

reset: function() {

count = 0;

return count;

}

};

}Step 6: Document Your Intent

Add comments explaining the closure:

/**

* Creates a rate limiter using closures

* Private state: lastCallTime (number)

* Returns: A function that only executes if enough time has passed

*/

function createRateLimiter(delayMs) {

let lastCallTime = 0;

return function(callback) {

const now = Date.now();

if (now - lastCallTime >= delayMs) {

lastCallTime = now;

callback();

} else {

console.log('Too soon! Wait a bit.');

}

};

}Conclusion

Closures might seem mysterious at first, but they're actually quite intuitive once you understand the core concept: functions remember where they came from.

What we've learned:

Closures happen when inner functions keep access to outer variables

They enable private data, persistent state, and elegant patterns

You're already using closures in callbacks, event handlers, and React hooks

Common pitfalls are easily avoided with let, careful scope management, and understanding references

Closures aren't exotic, they're fundamental to everyday JavaScript

Join the conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts and engage with other readers.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!