The Complete Guide to JavaScript Data Types and Structures: Master the Foundation of Modern Programming

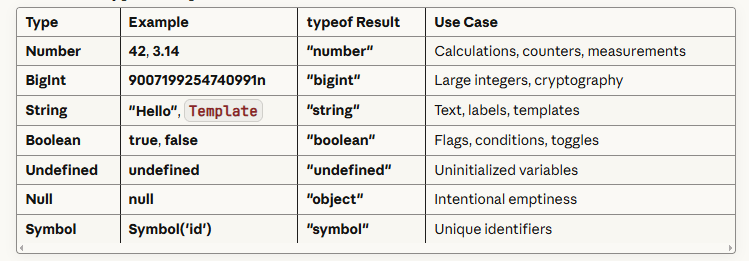

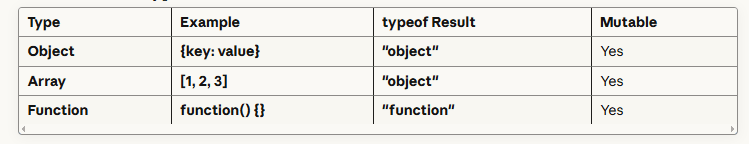

JavaScript has 8 fundamental data types divided into two categories: 7 primitive types (Number, BigInt, String, Boolean, Undefined, Null, Symbol) and 1 non-primitive type (Object). Primitive types store single values directly and are immutable, while objects store collections of data as key-value pairs and are mutable.

Understanding these data types is essential because they determine how JavaScript stores, manipulates, and processes information in your applications. The key distinction is that primitives are compared by value, while objects are compared by reference, a concept that affects everything from variable assignment to function parameters and memory management in your code.

Introduction: Why Data Types Are the Foundation of JavaScript Mastery

Every line of JavaScript you write depends on one fundamental principle: how your code stores and manipulates data. Whether you're building a simple form validation or architecting a complex enterprise application, understanding data types isn't just helpful, it's absolutely essential.

Here's the challenge most developers face: JavaScript's dynamic typing system offers incredible flexibility, but this same flexibility can introduce subtle bugs that are difficult to trace. A missing type check can cause a production failure. Misunderstanding the difference between primitive and reference types can lead to unexpected mutations in your application state.

This comprehensive guide will transform your understanding of JavaScript data types from surface-level awareness to deep, practical mastery. You'll learn not just what each data type is, but when to use it, how it behaves in memory, and how to avoid the common pitfalls.

Understanding JavaScript's Type System: The Two-Category Architecture

JavaScript organizes its data types into two distinct categories, each with fundamentally different behaviors and use cases.

Primitive Data Types: Immutable Single Values

Primitive types represent single, immutable values stored directly in the variable's memory location. When you assign a primitive value to a variable, JavaScript stores the actual value, not a reference to it.

Critical characteristic: When you copy a primitive value to another variable, JavaScript creates an independent copy. Modifying one variable has no effect on the other.

let originalPrice = 100;

let discountedPrice = originalPrice;

discountedPrice = 80;

console.log(originalPrice); // 100 (unchanged)

console.log(discountedPrice); // 80

Non-Primitive Data Types: Mutable Reference Values

Non-primitive types (collectively called "Objects") store references to memory locations rather than actual values. When you assign an object to a variable, you're storing a pointer to where the data lives in memory.

Critical characteristic: Copying an object variable creates a new reference to the same data, not a new copy of the data itself.

let originalUser = { name: "Sarah", role: "Admin" };

let modifiedUser = originalUser;

modifiedUser.role = "Editor";

console.log(originalUser.role); // "Editor" (changed!)

console.log(modifiedUser.role); // "Editor"

This fundamental distinction affects virtually every aspect of JavaScript programming, from variable assignment to function parameters, state management, and performance optimization.

The Seven Primitive Data Types: Deep Dive with Practical Applications

1. Number: JavaScript's Unified Numeric Type

Unlike many programming languages that distinguish between integers and floating-point numbers, JavaScript uses a single Number type for all numeric values. Internally, it's a 64-bit floating-point format (IEEE 754 standard).

Practical range: Safely represents integers between -9,007,199,254,740,991 and 9,007,199,254,740,991 (stored in Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER and Number.MIN_SAFE_INTEGER).

Special numeric values you must understand:

Infinity: Result of mathematical overflow or division by zero

-Infinity: Result of negative overflow

NaN (Not-a-Number): Indicates invalid mathematical operations

Real-world application example:

// Financial calculation requiring precision

const productPrice = 29.99;

const taxRate = 0.08;

const totalPrice = productPrice * (1 + taxRate);

console.log(totalPrice.toFixed(2)); // "32.39"

// Handling edge cases

const invalidOperation = "text" / 2;

console.log(invalidOperation); // NaN

console.log(typeof invalidOperation); // "number"

console.log(Number.isNaN(invalidOperation)); // true

Critical pitfall: Floating-point arithmetic can produce unexpected results due to binary representation limitations.

console.log(0.1 + 0.2); // 0.30000000000004

console.log(0.1 + 0.2 === 0.3); // false

// Solution: Use rounding or specialized libraries for financial calculations

console.log((0.1 + 0.2).toFixed(2)); // "0.30"

2. BigInt: Beyond Standard Number Limitations

Introduced in ES2020, BigInt handles integers larger than the Number type's safe range. Essential for applications dealing with cryptography, precise timestamps, or large-scale financial calculations.

Syntax: Append n to the integer or use the BigInt() constructor.

// Working with large integers

const largeNumber = 9007199254740991n;

const evenLarger = largeNumber + 1000n;

// Cryptocurrency wallet balance example

const satoshisPerBitcoin = 100000000n;

const bitcoinBalance = 5n;

const totalSatoshis = bitcoinBalance * satoshisPerBitcoin;

console.log(totalSatoshis); // 500000000n

Critical limitation: You cannot mix BigInt and Number types in arithmetic operations without explicit conversion.

const mixed = 10n + 5; // TypeError: Cannot mix BigInt and other types

// Correct approach

const result = 10n + BigInt(5); // 15n

3. String: Immutable Character Sequences

Strings represent textual data as immutable sequences of UTF-16 code units. Once created, a string cannot be modified, all string methods return new strings.

Three syntax options:

Single quotes: 'text'

Double quotes: "text"

Template literals:

text with ${variables}

Template literals (backticks) provide powerful features:

const userName = "Alexandra";

const itemCount = 3;

const totalCost = 47.50;

// Multi-line strings with embedded expressions

const orderSummary = `

Order Confirmation

------------------

Customer: ${userName}

Items: ${itemCount}

Total: $${totalCost.toFixed(2)}

Status: ${itemCount > 0 ? 'Processing' : 'Empty Cart'}

`;

console.log(orderSummary);

Common string operations:

const email = " USER@EXAMPLE.COM ";

// Chaining immutable operations

const cleanEmail = email.trim().toLowerCase();

console.log(cleanEmail); // "user@example.com"

// Substring extraction

const domain = cleanEmail.slice(cleanEmail.indexOf('@') + 1);

console.log(domain); // "example.com"

// Pattern validation

const isValidEmail = cleanEmail.includes('@') && cleanEmail.includes('.');

4. Boolean: Logical Binary Values

Booleans represent true or false values, forming the foundation of conditional logic and control flow.

Truthiness and falsiness: JavaScript converts values to boolean in conditional contexts. Understanding these conversions prevents logic errors.

Falsy values (convert to false):

false

0 and -0

"" (empty string)

null

undefined

NaN

Everything else is truthy, including:

"0" (string containing zero)

"false" (string containing the word false)

[] (empty array)

{} (empty object)

Practical application:

function validateUserInput(input) {

// Explicit boolean check

if (input === undefined || input === null || input === "") {

return { valid: false, message: "Input is required" };

}

// Using truthiness (less explicit, use with caution)

if (!input) {

return { valid: false, message: "Input is required" };

}

return { valid: true, message: "Input accepted" };

}

// Testing edge cases

console.log(validateUserInput("")); // invalid

console.log(validateUserInput(0)); // invalid (0 is falsy)

console.log(validateUserInput("0")); // valid (string "0" is truthy)

5. Undefined: Uninitialized Variables

Undefined indicates a variable has been declared but not assigned a value. JavaScript automatically assigns undefined to uninitialized variables.

let userPreference;

console.log(userPreference); // undefined

console.log(typeof userPreference); // "undefined"

// Function with no return statement

function processData(data) {

console.log(data);

// No return statement

}

const result = processData("test");

console.log(result); // undefined

Best practice: Avoid manually assigning undefined. Use null for intentional absence of value.

6. Null: Intentional Absence of Value

Null represents a deliberate assignment of "no value." Use it when you want to explicitly indicate emptiness.

let selectedFile = null; // Intentionally no file selected

function getUserById(id) {

const users = [{ id: 1, name: "John" }];

const found = users.find(user => user.id === id);

return found || null; // Explicitly return null if not found

}

The typeof null quirk: typeof null returns "object" due to a JavaScript implementation bug that can't be fixed for backward compatibility reasons.

console.log(typeof null); // "object" (confusing but intentional)

// Proper null check

if (value === null) {

console.log("Value is explicitly null");

}

7. Symbol: Guaranteed Unique Identifiers

Introduced in ES6, Symbol creates guaranteed unique values, primarily used as object property keys to avoid naming collisions.

// Creating unique symbols

const userId = Symbol('user_id');

const adminId = Symbol('user_id'); // Same description, different value

console.log(userId === adminId); // false (always unique)

// Using symbols as object keys

const user = {

name: "David",

[userId]: "12345", // Symbol key

[Symbol('role')]: "admin" // Another symbol key

};

console.log(user[userId]); // "12345"

console.log(Object.keys(user)); // ["name"] (symbols excluded)

console.log(Object.getOwnPropertySymbols(user)); // [Symbol(user_id), Symbol(role)]

Real-world use case: Preventing property name conflicts in shared objects or when extending third-party libraries.

Objects: The Non-Primitive Powerhouse

Objects are JavaScript's fundamental non-primitive type, storing collections of key-value pairs. Arrays, functions, dates, and regular expressions are all specialized object types.

Core Object Structure and Behavior

const employee = {

// Properties

firstName: "Michael",

lastName: "Chen",

employeeId: 10457,

isActive: true,

department: null,

// Method

getFullName: function() {

return `${this.firstName} ${this.lastName}`;

},

// ES6+ method shorthand

getStatus() {

return this.isActive ? "Active" : "Inactive";

}

};

console.log(employee.getFullName()); // "Michael Chen"

console.log(employee['firstName']); // "Michael" (bracket notation)

Reference vs. Value: The Critical Distinction

Understanding object references prevents countless bugs:

const originalConfig = {

theme: "dark",

language: "en",

notifications: { email: true, sms: false }

};

// Shallow copy - only copies first level

const configCopy = { ...originalConfig };

configCopy.theme = "light";

configCopy.notifications.email = false;

console.log(originalConfig.theme); // "dark" (unchanged)

console.log(originalConfig.notifications.email); // false (changed! nested object is shared)

// Deep copy solution

const deepCopy = JSON.parse(JSON.stringify(originalConfig));

// Note: JSON method doesn't preserve functions, undefined, or Symbols

Common Object-Based Structures

Arrays: Ordered collections with numeric indices

const priorities = ["Critical", "High", "Medium", "Low"];

priorities.push("Urgent"); // Add to end

priorities.unshift("Emergency"); // Add to start

const mediumIndex = priorities.indexOf("Medium");

// Modern array methods

const highPriorities = priorities.filter(p => p.includes("High") || p === "Critical");

const labels = priorities.map(p => p.toUpperCase());

Functions: First-class objects that can be assigned to variables

// Function declaration

function calculateTax(amount, rate) {

return amount * rate;

}

// Function as variable (function expression)

const calculateDiscount = function(price, percentage) {

return price * (percentage / 100);

};

// Arrow function (ES6+)

const calculateTotal = (price, tax, discount) => {

return price + tax - discount;

};

Addressing Common Challenges, Pitfalls, and Misconceptions

Challenge 1: Type Coercion Confusion

JavaScript automatically converts types in certain operations, leading to unexpected results.

String concatenation vs. addition:

console.log("5" + 5); // "55" (number converted to string)

console.log("5" - 5); // 0 (string converted to number)

console.log("5" * "2"); // 10 (both converted to numbers)

console.log("5" + 2 + 3); // "523" (left-to-right evaluation)

console.log(5 + 2 + "3"); // "73" (addition first, then concatenation)

Solution: Use explicit conversion or strict comparison.

// Explicit conversion

const userInput = "42";

const numericValue = Number(userInput);

const calculation = numericValue + 10; // 52

// Strict comparison

console.log(5 == "5"); // true (coercion happens)

console.log(5 === "5"); // false (no coercion)

Challenge 2: The var, let, const Confusion

Modern best practice: Use const by default, let when reassignment is necessary, avoid var entirely.

// const: Cannot reassign, but object properties can change

const config = { mode: "production" };

config.mode = "development"; // Allowed

// config = {}; // TypeError: Assignment to constant

// let: Reassignable, block-scoped

let counter = 0;

counter++; // Allowed

// var: Function-scoped, hoisted (avoid in modern code)

Challenge 3: Checking for Empty Values

Different types require different empty checks:

function isEffectivelyEmpty(value) {

// Null or undefined

if (value == null) return true;

// String

if (typeof value === 'string') return value.trim().length === 0;

// Array

if (Array.isArray(value)) return value.length === 0;

// Object

if (typeof value === 'object') return Object.keys(value).length === 0;

return false;

}

console.log(isEffectivelyEmpty("")); // true

console.log(isEffectivelyEmpty([])); // true

console.log(isEffectivelyEmpty({})); // true

console.log(isEffectivelyEmpty(null)); // true

console.log(isEffectivelyEmpty(0)); // false (0 is a valid number)

Actionable Implementation: Type-Safe JavaScript Patterns

Step 1: Implement Runtime Type Checking

function processPayment(amount, currency, userAccount) {

// Validate types explicitly

if (typeof amount !== 'number' || amount <= 0) {

throw new TypeError('Amount must be a positive number');

}

if (typeof currency !== 'string' || currency.length !== 3) {

throw new TypeError('Currency must be a 3-letter string');

}

if (typeof userAccount !== 'object' || userAccount === null) {

throw new TypeError('User account must be an object');

}

// Process payment with confidence

return {

processed: true,

amount: amount,

currency: currency.toUpperCase(),

accountId: userAccount.id

};

}

Step 2: Use Type Guards for Complex Checks

// Type guard function

function isValidUser(obj) {

return obj !== null

&& typeof obj === 'object'

&& typeof obj.id === 'number'

&& typeof obj.email === 'string'

&& typeof obj.isActive === 'boolean';

}

// Usage

function sendNotification(user, message) {

if (!isValidUser(user)) {

console.error('Invalid user object provided');

return false;

}

// Proceed with confidence

console.log(`Sending to ${user.email}: ${message}`);

return true;

}

Step 3: Leverage typeof for Defensive Programming

function safelyAccessProperty(obj, propertyPath) {

if (typeof obj !== 'object' || obj === null) {

return undefined;

}

const keys = propertyPath.split('.');

let current = obj;

for (const key of keys) {

if (typeof current !== 'object' || current === null || !(key in current)) {

return undefined;

}

current = current[key];

}

return current;

}

// Usage

const data = { user: { profile: { name: "Sarah" } } };

console.log(safelyAccessProperty(data, 'user.profile.name')); // "Sarah"

console.log(safelyAccessProperty(data, 'user.address.city')); // undefined

Comprehensive Data Types Quick Reference

Primitive Types Comparison

Non-Primitive Types

Practical Mini-Project: Data Type Validator System

const userRegistration = {

username: "tech_dev_2024",

email: "developer@example.com",

age: 28,

isVerified: true,

registrationDate: null,

preferences: {

newsletter: true,

theme: "dark"

},

skills: ["JavaScript", "Python", "SQL"]

};

function validateRegistration(data) {

const validations = [];

// Username validation

if (typeof data.username === 'string' && data.username.length >= 3) {

validations.push({ field: 'username', status: 'valid', type: typeof data.username });

} else {

validations.push({ field: 'username', status: 'invalid', type: typeof data.username });

}

// Email validation

const emailRegex = /^[^\s@]+@[^\s@]+\.[^\s@]+$/;

if (typeof data.email === 'string' && emailRegex.test(data.email)) {

validations.push({ field: 'email', status: 'valid', type: typeof data.email });

} else {

validations.push({ field: 'email', status: 'invalid', type: typeof data.email });

}

// Age validation

if (typeof data.age === 'number' && data.age >= 18 && data.age <= 120) {

validations.push({ field: 'age', status: 'valid', type: typeof data.age });

} else {

validations.push({ field: 'age', status: 'invalid', type: typeof data.age });

}

// Skills array validation

if (Array.isArray(data.skills) && data.skills.length > 0) {

validations.push({ field: 'skills', status: 'valid', type: 'array' });

} else {

validations.push({ field: 'skills', status: 'invalid', type: typeof data.skills });

}

return validations;

}

const results = validateRegistration(userRegistration);

console.log('Validation Results:', results);

// Output example:

// Validation Results: [

// { field: 'username', status: 'valid', type: 'string' },

// { field: 'email', status: 'valid', type: 'string' },

// { field: 'age', status: 'valid', type: 'number' },

// { field: 'skills', status: 'valid', type: 'array' }

// ]

Conclusion & Final Takeaways: Building on Your Data Types Foundation

Mastering JavaScript data types is not about memorization, it's about understanding behavior. The distinction between primitive and reference types, the nuances of type coercion, and the patterns for type-safe code form the foundation for writing reliable, maintainable JavaScript applications.

Key principles to remember:

Primitives are compared by value; objects are compared by reference: This single concept prevents countless bugs in real-world applications.

Use explicit type checking and conversion: Don't rely on JavaScript's coercion behavior in production code. Be intentional about types.

Choose the right data structure for your use case: Use objects for key-value associations, arrays for ordered collections, and Sets for unique values.

Favor const over let, and never use var: Immutable-by-default reduces bugs and makes code easier to reason about.

Understand typeof limitations: Know when to use typeof, when to use Array.isArray(), and when to check for null explicitly.

Next steps in your JavaScript journey:

Practice type coercion scenarios: Experiment with operations that mix different types until their behavior becomes intuitive.

Explore TypeScript: If type safety is critical for your projects, TypeScript adds compile-time type checking to JavaScript.

Study memory management: Understanding how primitives and objects are stored helps you write more performant code.

Build type validation utilities: Create reusable functions that validate and sanitize user input in your applications.

Take action today: Open your code editor and refactor one of your existing projects to use more explicit type checking. You'll immediately see fewer runtime errors and more predictable behavior.

The difference between a junior developer and a senior developer often comes down to understanding these fundamentals deeply. You've taken a significant step forward today.

Next article : JavaScript loops

Join the conversation

Sign in to share your thoughts and engage with other readers.

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!